1.Artificial intelligence has become a school troublemaker. Not every child will go home and write 800 words on “Macbeth” when Chatgpt can do it for them. In Turkey and the Netherlands, experiments using large language models (LLMS) to teach coding and maths ended with mixed results: some pupils became so dependent on the LLM that, when it was removed, they performed worse than classmates who had never used it. Teachers, too, have learned to cheat. Students complain that some educators are using bots to churn out generic feedback on their work.

2.In the rich world, AI and other e-learning tools have yet to prove better than traditional teaching. Chatbots can get sums wrong and invent facts. In America, tech-infused private and charter schools briefly flourished in Silicon Valley only to fade without rigorous evaluations.

3.But in poorer countries, where classrooms are overcrowded and teachers scarce, low-cost teaching aids provide a real opportunity. One in six children across the world live in extreme poverty (or less than $2.15 per day). In low- and middle-income countries an estimated 70% of ten-year-olds cannot read a simple story in any language. In sub-Saharan Africa the figure is closer to 90%. A working paper published in May by the World Bank suggests that AI may offer a partial solution.

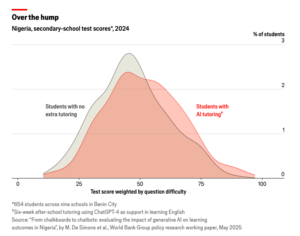

4.The study followed 422 secondary-school students in Nigeria who took part in 12 90-minute after-school sessions over six weeks. Pairs of pupils, supported by a teacher, interacted with Microsoft Copilot, a chatbot based on gpt-4, to improve their English grammar, vocabulary and writing skills.

5.The results were striking: by the end of the six weeks the children in the ai “treatment” group had made progress equivalent to nearly two years’ worth of their regular schooling, according to Martín De Simone, who led the study. Overall, the ai group’s test scores were about 10% higher than the control group’s (see chart 1).

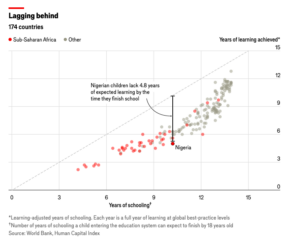

6.In end-of-year exams—which covered topics beyond the chatbot’s material—they still did better than their peers. (The final tests were done with pen and paper; the results reflected the children’s actual learning, not their use of the tool.) This might be, in part, a reflection of how poor the baseline is. Around the world, children typically learn less than what their time in school implies (see chart 2).

The article mentions Nigeria, Turkey, and the Netherlands. What do you think are some differences between education in those countries and Japan?

7. On average, children in Nigeria receive ten years of schooling by the age of 18, according to the World Bank. But their learning outcomes are equivalent to roughly half of what might be expected. In countries with better-resourced schools, the same intervention with AI might yield more modest results.

8. The findings also come with other caveats. At $48 per student, the programme was relatively cheap, though still more than the monthly minimum wage in Nigeria. The study could not fully isolate the effect of the chatbot from that of any extra study time with a teacher. And scaling up would require a stable internet connection and access to devices—neither of which is guaranteed.

9. Some education reforms, although controversial, have succeeded by tightly standardising lesson plans without the need for extra technology. Even so, the pilot programme outperformed 80% of more than 230 other education programmes in low- and middle-income countries. That should interest governments and donors seeking to improve basic skills in struggling school systems.