(Clockwise from left) Yoshihisa Aono, founder and CEO of Cybozu, moderates an online discussion with Julia Behrends, customer support at online travel agency Voyagin; Aaron Fowles, assistant manager of global communications at Toyota Motor Corp.; and Shin Ki-young, a professor of political science and gender studies at Ochanomizu University.

Warm up

—- * * FOR NEW STUDENTS ** ————————————— ————

- What industry do you work in and what is your role?

- What are your responses in your role / position?

- Can you describe to the function of your workplace / company?

- How many departments, how many offices. National or International?

- What are the minimum requirements for employment ie Education or Experience?

- How many opportunities are there to ‘move up the ladder’?

- What is the process for changing job roles ie Interview? Test?

————————————————– —— ——————————————– ——- —

General discussion about your workweek:

- Current projects? Deadlines? Opportunities?

- Anything of interest happening?

————————————————– —— ——————————————– ——–

Script

1.

American Aaron Fowles, assistant manager of global communications at Toyota Motor Corp.; German Julia Behrends, customer support at online travel agency Voyagin; and South Korean Shin Ki-young, a professor of political science and gender studies at Ochanomizu University have roughly 14 years between them working in Japan. While their experiences navigating the local working culture may vary, they all have valuable insight into surviving and thriving as a non-Japanese worker in Japan. They graciously shared advice with the ever-curious Yoshihisa Aono, founder and CEO of the Japanese software firm Cybozu.

* Opinions do not reflect the view of their companies

2. Aono: Thank you for coming. As my company expands into the global market, I’m interested in learning how to make our work environment more friendly to international staff. Based on your experiences, what difficulties have you faced working in Japan?

3. Fowles: It’s difficult to accept the Japanese idea of work-life balance. American people work to enjoy our lives. We treasure time with our families.

Of course, Japanese people cherish their families, too, but they’re more willing to sacrifice family for work. This creates pressure within the office to work longer hours. As a result, I sometimes feel guilty for leaving the office on time, even though I’ve finished my work.

4. Behrends: German people also cherish their families and would rather go home when they finish their work.

5. Shin: South Korea is more similar to Japan in that regard. Societies that put excessive value on staying at work are usually dominated by male culture, where men work outside and women stay home. The idea that men should be the main breadwinners and work as hard as possible while women stay at home remains strong in male-dominated workplaces. In contrast, Ochanomizu is a women’s university, where half of the professors and many of the staff members are women. We have achieved a better work-life balance that allows us to go home when we wish.

Structure and promotion

6. Aono: What do you think of the pyramidal structure and seniority system at many Japanese institutions?

7. Shin: Strict hierarchy generates a culture where junior members are encouraged to toe the line and accept seniority-based promotion while not causing trouble. That can harm the openness of the entire organization.

8. Behrends: Startup companies such as mine, Voyagin, are not that pyramidal. They are small and the presidents are young, which encourages more horizontal relationships. That may however change when they grow larger. Our company was bought by Rakuten, and I’m looking forward to seeing how things work at a larger company.

9. Fowles: It takes time to earn the trust of your boss and new colleagues in Japan. Until you earn that trust, you may not be assigned jobs that match your professional ability. I worry that foreign staff may end up feeling frustrated if Japanese companies don’t make full use of their abilities. Additionally, Japanese bosses tend to develop relations among team members through unofficial social interactions. A good example is after-work drinking parties, known as nomikai. While attendance is rarely mandatory, it’s a practical necessity to build trust and good relations with your team.

Key for building trust

10. Aono: It’s interesting you brought up nomikai. I remember 25 years ago, when I was at Panasonic Corp., part of the boss’ job was to take subordinates for drinks. I felt obligated to go drinking several times a week. What do you think about nomikai culture?

11. Fowles: I don’t drink. Instead, I enjoy having dinner with colleagues as a way of building our relationship. I won’t accept every time, nor will I stay late, since I want to get home to my family.

12. Behrends: Nomikai culture is not so prominent at Rakuten. When I’m invited, I’ll go if I feel like it.

13. Shin: At our university, we only have parties once or twice a year. It’s a little lonely because we seldom have private conversations among colleagues. People don’t speak openly at official faculty meetings, and while I sometimes conduct one-on-one meetings with my staff, they don’t speak frankly, either.

14. Aono: What do you need to maintain good relationships with your Japanese superiors and colleagues?

15. Shin: It’s difficult. I think the key is the leader’s communication style. If the leader listens to team members and gives appropriate feedback, that can lead to a positive atmosphere within the group.

16. Shin: It’s difficult. I think the key is the leader’s communication style. If the leader listens to team members and gives appropriate feedback, that can lead to a positive atmosphere within the group.

17. Behrends: For me it’s about respect on an equal footing.

18. Fowles: I’ve found that Japanese superiors provide generous support, even to those who are not their direct subordinates. They serve as mentors, taking time to answer general questions from junior members. Perhaps this is the byproduct of Japan’s notoriously long working hours, but that kind of unofficial support is one of the good aspects of Japanese work culture.

19. Shin: I agree on the importance of mentors. I remember only being able to progress as a scholar thanks to the mentorship of a senior professor working in the office next door. She would always be available to listen to my problems and we discussed various things other than work.

20. Fowles: To build trust, it’s important to talk about things other than work. That’s why I think, especially as a foreigner, it’s important to make time for casual lunches with colleagues.

https://info.japantimes.co.jp/jt-with-kintopia/02/

Discussion

1. Have you ever worked with foreign people before? What was that experience like?

2. How do you imagine foreign workplaces and their subsequent cultures to be like? Are there any stereotypes you have heard?

3.

What would be your advice for a foreign person entering a Japanese company?

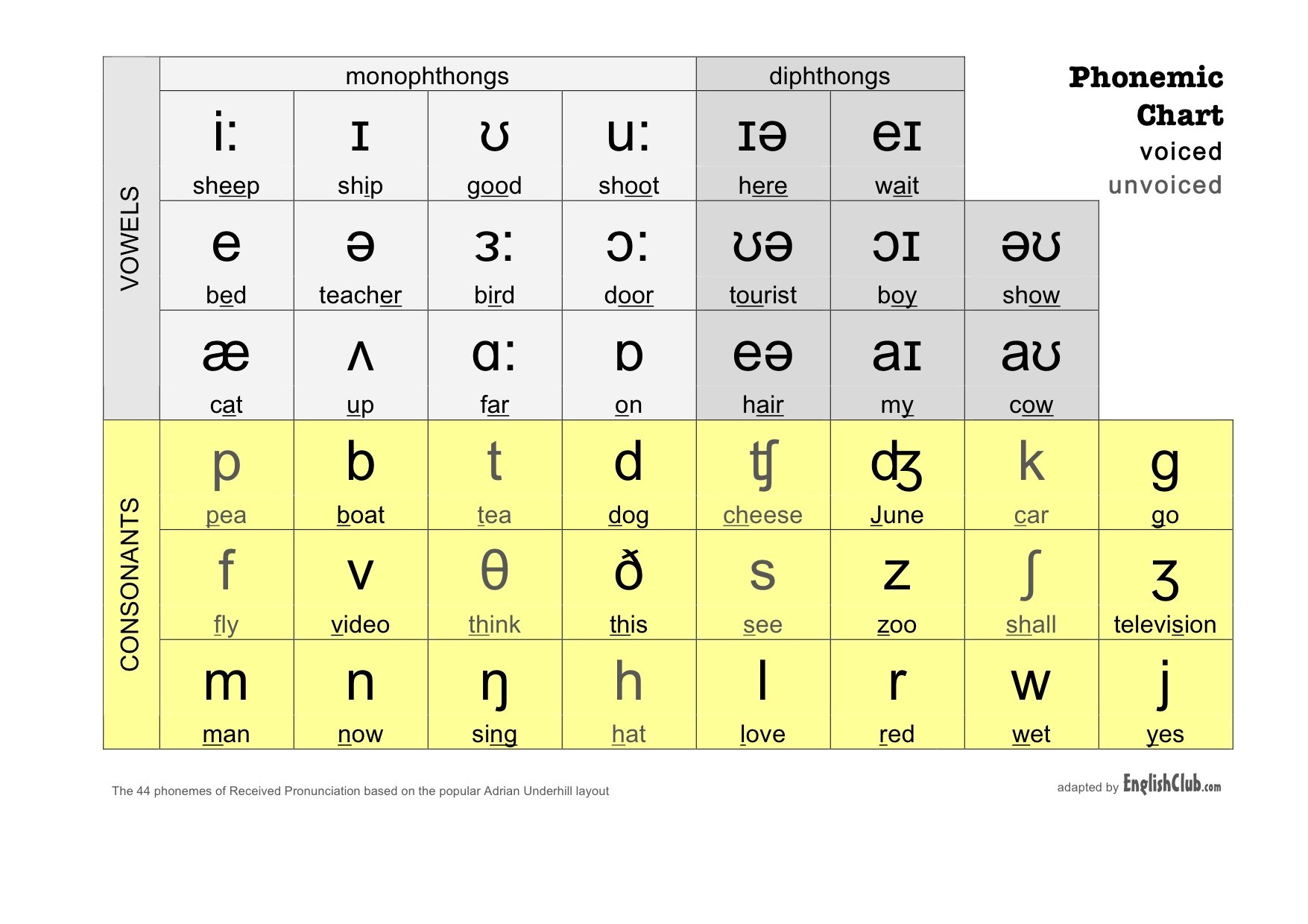

Phonetic Chart